Customer Value Mapping (Business Value Mapping)

How to Make Marketing and Selling Easier

By Michael J Webb

You know the drill. A new product is launched, one that does something useful and performs well. Millions of dollars in development and people’s careers are staked on its success. There are even some customers who positively love it.

But it doesn’t sell—at least, not enough. Sales presentations don’t lead to deal-making. Special sales training fizzles. Sales and marketing begin blaming each other. Everybody loses.

A company I know (I’ll call it Mega International) repeated this pattern over and over again. Dedicated to high quality, Mega made sure that its products always met specifications. The people at Mega knew that their line of electrical controls helped customers’ manufacturing machines run better. Mega’s salespeople knew that meant their customers could make more money… somehow.

Unfortunately, they had a lot of trouble with the “somehow” part. The company’s original products were designed with electrical engineers in mind. But the company’s new products had enormous potential benefits beyond the electrical and maintenance engineering departments.

The company’s sales training programs still taught everything there was to know about cycle times, I/O addressing, and programming languages. But it did not explain how salespeople could help their customers make more money with the new systems. This scenario happens far too frequently in all kinds of industries.

In his famous essay on business management, “Marketing Myopia” (Harvard Business Review, 1975), Theodore Levitt argued that the decline of businesses is usually not due to outmoded technologies, or even to changing markets and tastes. Instead, he said, growth stops and decline begins because top managers focus too narrowly on their existing product niche. He illustrated this insight with examples from many industries, most notably railroads, who “assumed themselves to be in the railroad business rather than in the transportation business.”

In other words, railroad industry leaders focused on their own products rather than on what their customers wanted. Levitt pointed out that a corporation must be viewed as a customer-creating and customer-satisfying organism. Management must focus first on securing and evolving with customers, and second on producing goods or services.

However, most top managers focus first—and perhaps only—on producing goods and services in their company’s existing market niche. What can be done to help companies avoid this dead end?

Selling to the “Wrong” People

The customer’s production department often had the most to gain when Mega International launched a new product, or when it attempted to integrate its components into a major system. But salespeople were used to calling on engineering and maintenance departments. Calling on production operations presented significant challenges for Mega International sales people:

- They were not fully prepared to speak the language of production.

- Calling on people other than their usual contacts might arouse suspicion, even resistance.

- They didn’t know how to determine if a production manager really needed the product.

- They couldn’t answer questions about the systems expertise needed to install it.

All these barriers made for a potentially long, complex selling effort that could well have been a waste of time.

Salespeople knew the district sales managers would have little patience for it. Most salespeople figured they were better off sticking with what they already knew. They showed the new widgets to the same engineering and maintenance contacts who bought the old ones. If they didn’t sell, well, whose problem was that?

And so it went. Product divisions worked their hearts out creating new and innovative products, many of which were dashed upon the shoals by a sales force unable to leverage their potential.

Who Is Responsible for Making Sales Easier?

Few people within Mega International could see the lack of alignment among key functional groups—including, most tragically, the lack of alignment between the sales force and their customers.

Those that did were not powerful enough to do anything about it. Senior management seemed uninterested despite the fact that this pattern, in which good products didn’t sell, kept recurring. Orders produced by the few salespeople who could close these “difficult” deals failed to reach critical mass. Projected revenues for new products did not materialize. Ultimately, waves of layoffs ensued.

This kind of situation is far too common, especially where technology continues to make new products and services possible. Whose job is it to prevent these situations? Who is accountable for redefining what is valuable to customers, designing effective new ways of helping them buy, and getting these new processes implemented in the field?

In short, whose job is it to make sales easier? In most companies, neither the marketing nor the sales department has the skills, the motivation, or the accountability to do it. The fact is that in many companies no one is accountable for this crucial task! Is it any wonder that Mr. Leavitt’s observation remains true in so many companies today?

The Need for Customer Value Mapping

Traditional approaches to defining customer value just aren’t good enough in today’s technologically complex, highly diversified marketplace. Here’s why:

- Market research identifies trends that are too general to guide specific selling strategies.

- Focus groups don’t necessarily probe the right issues or translate them into actionable steps for producing sales results.

- “Voice of the Customer” and “Quality Function Deployment” initiatives microscopically focus on the stitches of detailed product features and characteristics. They often fail to deal with the fabric – the business context driving the customer’s desires, goals, and objectives.

- Features and benefits identify your company’s idea of what is important about your products and services, but usually don’t reflect much insight to your customers’ point of view.

A more systematic approach is needed, one that enables companies to understand value from their customers’ point of view, and at the right level of detail. Customer Value Mapping is such a method, because it begins with insight into “value.”

To really understand value, you must ask, “To whom is it valuable?” and “For what is it valuable?” This means, “Which people within the customer organization might you impact?” And, “What are those individuals trying to accomplish?” As a starting point, a simple organizational chart helps to identify individuals that your product can help, and at what level your product’s impact could be felt.

Mega International needed to shift its selling focus from engineers and maintenance managers to production managers. A tiny improvement in the yield of existing production machines can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars to the production department. The real issue was not “Is it hard to program?” (the maintenance engineer’s concern), or even “Can we determine precisely what improvement might result?” (the quality manager’s concern). These questions were legitimate, but they should not have been barriers to a sale—as long as the production manager recognized the potential impact of the new control product.

Understanding what the production manager values requires a customer value map, such as the one shown in Figure 1. The value map captures the main objectives, metrics, strategies, and issues a production manager typically faces. To create the map, you must focus on understanding the production manager’s business apart from any impact your company might have. After the individual’s context has been defined, you can begin identifying where your products and services might offer significant impact (indicated by italics).

Figure 1 illustrates in italics where the controller impacts the production manager’s world

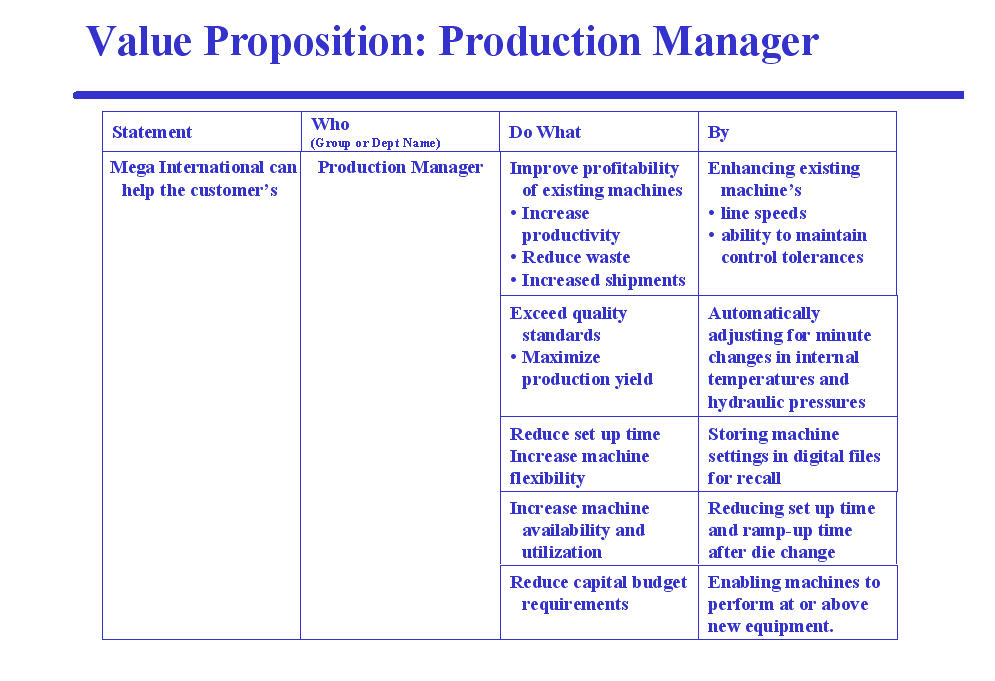

Understanding the context in which your products and services can have impact is critical to uncovering what is valuable to the customer. The next step is to develop statements which describe your potential impact. These statements can be grouped and massaged into a Value Proposition Table, like the one shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates clear value propositions for the Production Manager.n in Figure 2.

These statements are hard-hitting because they clearly articulate how the product impacts production manager. Completing these exercises for each of the key players in the customer’s organization allows precise analysis of the interests of various departments and levels of management. The most powerful insights are uncovered when real customers assist marketing and sales managers in mapping value in their organizations.

The resulting knowledge becomes a sort of instruction manual for how the customer’s business really works—an invaluable resource which marketing departments long for, but usually can’t generate on their own.

In addition to facilitating all kinds of marketing communications, the maps form a template for prioritizing a hierarchy of customer value. Countless salespeople struggle in complex sales environments because they fail to leverage the right issues. Most sales people have to develop “instincts” for how to sell to various customers through years of hard field experience rather than through training courses, because no one can articulate what they need to know.

The hierarchy of value revealed by the customer value map can help identify who salespeople should be talking to and what they should be looking for. It is the foundation for designing an appropriate and effective sales process. Further, it provides a more powerful base for the seller to negotiate from.

Consider this list of critical sales tools and training materials that can be developed once the customer value map has been defined:

- Key players with whom the salesperson should have a relationship

- Lists of high-impact questions to help the salesperson uncover value

- Scripted presentation examples, sample proposals, and case studies illustrating issues critical to customer value and the customer’s perception of quality

Tools like these can be used to tailor sales training products, making them more usable in the field. They can be used to help new salespeople come up to speed faster, validate the thoroughness of experienced salespeople, and even identify specific reasons why some salespeople are more successful than others. They provide a template for marketing departments to use in helping sales people do their jobs.

Customer Value Mapping helps clarify the intermediate objectives salespeople need to accomplish in working with prospects and customers. It sheds light on what might make salespeople’s jobs easier, rather than adding to their burdens as often happens (for example, consider the effect of many CRM software initiatives). In addition to product-focused material included in most product launches, customer value maps and the selling tools that can be produced from them provide the critical linkages sales people need to become effective in the field more quickly.

Applying Customer Value Mapping in Your Organization

By applying the analytical thinking style of the quality movement to the realm of marketing and sales, Customer Value Mapping establishes a common language for understanding what customers value—and why. It is a necessary foundation for designing and improving processes to find, gain, and keep customers.

Customer Value Maps reveal one reason why a sales force trained to sell to one type of customer cannot easily begin selling to a different one. The key barrier is the knowledge required for salespeople to be effective. Had this approach been used at Mega International, senior managers might have seen why sales results were poor.

Value maps for new products would have illustrated the disconnect with their traditional value proposition. This insight could have informed their decisions regarding resources, training, and sales tools to create a faster ramp-up in volume. Customer Value Mapping has been used by dozens of companies to create powerful strategies to reach customers and build bottom-line results:

- An engineering firm thought they were releasing a new service offering to a large cohesive market of potential prospects. Customer Value Mapping helped them realize they were really selling to small markets with divergent value propositions. This insight enabled them to channel their resources differently, avoiding a costly mistake.

- A technically oriented manufacturer of microbal testing systems for food plants learned some surprises during a value mapping session. They been overlooking operational savings produced by their products. In addition, however, they learned that food plant employees liked to give plant tours to their customers because showing off their latest testing equipment made them look good—a benefit that had been completely overlooked!

- A regionally focused garment services company transformed its sales culture by gaining an understanding of what motivated its customer’s senior executives. Value mapping produced sales tools that enabled salespeople to feel they “had the right” to talk with senior-level management.

- A large consulting company launched a tremendously successful telesales initiative with an outside telemarketer. Value mapping helped the telemarketer to become effective selling its high-margin materials to low-volume accounts, achieving substantial results within a few months.

Summary

To achieve Theodore Leavitt’s goal of becoming “customer-creating and customer-satisfying organisms,” companies need a systematic way to generate and leverage first-hand knowledge of what customer businesses value. This means answering the questions, “Value to whom, and for what?” Customer Value Mapping provides powerful insight about your customers—insight that can be a foundation for

- Designing and improving your strategies for finding, gaining, and keeping customers

- Developing more effective selling tools and training aids for existing products

- Developing new and more valuable products and services

In 1979, industry pundit Phillip Crosby wrote, “Quality is meeting customer requirements.” (Quality Is Free, McGraw-Hill, 1979). Applying the quality profession’s analytical mindset to defining what customer’s value is something most quality gurus would applaud. Customer value does not stop with steel or plastic or silicon, with specifications, functional requirements, or even with an RFP. Customer value extends to applications, to changed business processes, and to people’s objectives, issues, relationships, and perceptions as well.