Sales Process Training

Sales Process Training Program

[accordion] [title]Align the Goal and the Team for Success – Overview[/title] [details]Thinking carefully about how to align the goal and the team for success is a wise investment.

First, consider the most likely causes for the failure of improvement initiatives:

- Inappropriate (lousy) mission, not viscerally sponsored by management

- Involving the wrong people

- Poor project planning, usually lack of resources, or lack of time

Inappropriate mission

Targeting the mission incorrectly is a surprisingly common problem. People who study military history learn how often armies have attacked the wrong hills, or even the wrong countries. Some have occasionally not known when to stop and declare victory. Others failed to realize when their mission had drifted. Similar problems occur in business, and for the same reasons.

Management can be very good at backing things but often may back too many things at one time. Then they dump the things they really weren’t too thrilled about in the first place. Executives must carefully consider and prioritize the problems they are trying to solve. We will present some guidance around how to think about and select your improvement theme and mission most productively.

Involving the wrong people

People make things happen, as they say, but not always purposeful things. To make purposeful things happen, you need the right people, well led, and committed. There is a structure to the kind of talent needed for generating and sustaining improvement The procedure we will describe offers criteria for making the right people selections.

Poor planning

While we all tend to feel we are “better than average,” at many things, few people are natural problem solvers, able to separate fact from assumptions and zero-in immediately on root causes that will enable improved performance and for gains to be sustained. Most of us have to learn by trying and failing, sometimes learning very little over long periods of time.

An improvement frame is a template designed to help prevent the most likely causes of failure in improvement initiatives. It is intended to encourage everyone on the team to think carefully through the foundations of the problem and the potential solution.

Conducting successful improvement

A failure in any of the three foundational areas above may not be recoverable without major embarrassment. However, there are an array of obstacles to overcome, all stemming from the nature of the problem, the nature of the people, and the nature of the thinking required to succeed.

In this series, we present an overview of what successful improvement looks like:

- Selecting the goal/ theme for improvement

- Understanding problems and problem statements

- Selecting people for improvement team roles

- Understanding the Concept of Catch Ball

- Using an improvement frame

- Launching an improvement initiative

The procedures we will present ensure your businesses has the best chance of selecting the right targets, of engaging the hearts and minds of the right people, and of solving the problem in a way that can be permanently sustained.

[/details] [title]Selecting the Goal/Theme for Improvement[/title][details]Developing the goal and problem statement is perhaps the most critical work a sponsor or team leader can do to enable success. This especially the case when first establishing an improvement policy within an organization. In the early stages, when everyone wonders what “process excellence” means, choosing the wrong problem can be quite damaging.

- Choose a problem that is too difficult, and your team can flounder, or take too long.

- Choose a problem that is too easy, and your effort might be seen as to trivial to matter.

Everyone wants to solve big problems so they can be a hero, but solving them effectively, in reality, is usually a matter of choosing your battles carefully.

The first battle is to apprehend the problem correctly. Businesses are extremely complex systems, and individual people rarely understand all of the dimensions of a problem needed to solve it in a way that it can stay solved, and also avoids unintended consequences.

In “Sales Process Excellence” we pointed out that there are three categories of causes within a business (page 118):

- Voice of the Business (VOB): This is what management and the owners want – revenue, profit, growth, market share, and so on – like the Theatre Owner in Chapter 4. VOB is often cound in the financial reports and other standard reports of the business.

- Voice of the Customer (VOC): This is the customer’s experience of the business – their wants and needs and whether the business is fulfilling the – like the example of the Miyako Hotel in Chapter 4. The customer’s perception of value is what allows the business to make money.

- Voice of the Process (VOP): This data emanates from the processes themselves, from process results and variations. I include in this the employees’ experience of the process in their efforts to meet targets, and their problems and frustrations, instances of rework and so on (sometimes called Voice of the Employee, or VOE).

Broadly speaking, a business works when it is able to reconcile the conflicts of interest between these three voices. Process excellence is the method of identifying the nature of these conflicts and solving them. Process excellence and continuous improvement are about real sustained improvement in the business’ ability to perform. It is not about creating the illusion of improvement based on one marketing victory or a lucky win or a bluebird sale.

The key is learning to make linked improvements that stick, hitting lots of successful “base hits” (small improvements) so you don’t have to depend on a grand slam or a government loan (not an option for most of us). Of course you want to achieve the targeted improvement for the business. But continuous improvement is never one improvement; it is an entire system of layered improvement that you and your employees can master and achieve every day, not just on some ad hoc or one-time project.

Types of problems

Years ago, a well meaning but poorly trained engineer named Sam was puzzling over a tricky problem with a malfunctioning machine in his plant. He reported about the problem to the plant manager.

“I haven’t figured this problem out yet, boss,” he said as he scratched his head.

The plant managers said, “Well, OK, so is it a mechanical problem?”

“No … no, it is not mechanical. The thing is working fine mechanically.”

“Well, then,” his boss asked, “Is it electrical?”

“No … that checks out too.”

The plant manager hesitated for a moment, “Well, damn it Sam!” he exclaimed. “What the hell is it? Spiritual?”

The nature of problem solving is to identify what is true and what isn’t true. Obviously, in addition to mechanical, and electrical problems, there are people problems and technical problems, and all sorts of other things. For our purposes in process excellence, where we are trying to generate more output with less input to the production system, there are three types of problems (these are described in detail in “Sales Process Excellence” page 119):

- Problems that are too large

- Problems in which there is no process

- Problems in which the process is not capable (common cause)

- Problems that come and go (special cause)

Selecting the right problem

If you are an executive or team leader in the early stages of initiating process excellence in sales and marketing, it is important to think carefully about the kind of problems you have, and which of these might be appropriate for an improvement initiative.

- What kinds of issues seem to plague the business? These should be things that would be felt immediately if they were solved.

- Think about what you know regarding the VOB, VOC, and VOP. Where within this network of causes and effects do you think the root cause might be? How do you know this (what data do you have that suggests this)?

- What kinds of things might people in your business actually have some control over? Do they agree?

Look ahead and imagine success; what it will feel like and what you will point to as having gone well; and how you will keep the gains intact? What, specifically, will be different in everyone’s world if the problem is solved? Another way of thinking about this is to ask how will you know when the problem is solved? What measurements would change?

Some people who are new to process excellence have a tendency to think broadly around topics like “innovating a new product” or “winning new customers.” However valuable such endeavors

might be, they are not process excellence. Process excellence functions at a very granular level, forcing people to define their problems very precisely, tying their analysis to observed data and evidence, ensuring the problems get solved in a measurable (provable) way, and that the problems stay solved.

Often senior level people do not have the first hand knowledge to be able to define a problem at the appropriate level of detail, but the do have first hand knowledge of the business goals and challenges the organization needs to meet. The essence of good leadership is for these business leaders to engage others in the business in a way that energizes them to get the problems solved.

This is done by means of problem statements, selecting the right people, and catch ball.

[/details]

[title]Understanding Problems and Problem Statements[/title][details]Problem statements

If a problem statement is not right for the situation or is poorly stated, you might select the wrong team leader, or make the task impossibly big. If you have no experience in improvement at all, it is best to start small.

Simply ask “What are the actual results from the work of selling that we are not happy with?” The answer could be such things as:

- “Market share has declined for three years in a row.”

- “Customer attrition in the first year exceeds the industry average by 60%.”

- “The average cost of making a sale has increased 25% in two years.”

- “Customer returns for the last quarter are the highest ever recorded.”

- “Our average sales cycle has gone from 42 days to 54 days in the last 12 months.”

- “Our last 2 product launches have not gone well in the SE region.”

The above are clear signals you can extract from a world of background noise. It is what you are confident is true, or at least true enough to get started in the right direction.

Avoid Naming Problems Early On

The worst thing you can do is start naming “problems.” American culture often confuses problem statements with assumed solutions. Someone once told me the “problem” was “We have not fired Fred yet”! Others might say things like the “problem is our CRM system is antiquated”, or “our product is no longer unique”.

These may turn out to be true, and may actually be relevant, but are very risky as a starting point as they can promote group think, cause the team to overlook important information, and can kill ideas. They may not be root causes of your real problems. Start simply with clear signals of what is unsatisfactory in business results, preferably quantifiable. (Of course, this is the role of UDRs, undesirable results, which we will discuss in the next section. )

Measurement improvement as a possible starter theme

More than one executive has told us that they “have no clear signals to read, it’s just all screwed up.” If you are one of these, then you should turn your attention to the measurement system you are using and consider that as your first attack. You may be amazed to find out:

- People normally use very different definitions for what they are observing and measuring.

- Measurements are often biased or distorted for various purposes.

- The methods of data capturing can vary from person to person, or region to region.

- Accountants may have designed your measures for themselves, and not for you.

- Data is not accurately time related to defined periods.

The data has no predictive value to management, only reactive or historical.

Make no mistake, going from unmeasured to measured in sales and marketing is a major breakthrough achievement. Measurement is always a subject in improvement initiatives, and you can target certain aspects of measurement for small improvements as well, and achieve very large gains. You may want to pick a few vital measures at first to improve the accuracy, precision, and timeliness of your management information. You will want to reduce the measurement error, bias, and drift over time in your data.

Definition of the word “problem”

A problem is the poor or undesirable result of a job, an activity, or a process. Unfortunately, especially in North America, the word is often used interchangeably to mean potential causes or solutions. And example is a statement such as “The problem with my sales process is my salespeople need sales training.”

The term UDR (undesirable result) is used to help us think and communicate more clearly about problems. It is one of the most important concepts in Sales Process Excellence. The reason is UDRs help clarify everyone’s thinking, from entry level employees all the way up to the Chairman and CEO.

UDRs focus your mind on the reality of evidence and data, which is at the root of successful problem solving. If the UDRs are well defined you can verify (and clarify) them with data. This is powerful preparation for beginning to investigate why the UDR is happening.

Examples:

- I did not meet my sales quota.

- My customers don’t understand what we do.

- I can’t get to the real decision makerquick enough.

- It takes too long to get the drawings from engineering.

- It takes too long to get credit approved for the customer.

- Our products are too expensive.

- I don’t get enough sales leads from marketing.

- The customeronly cares about price per unit.

- My prospectwon’t return my calls.

UDR’s stop us from achieving our goals and objectives. If you are a salesperson, what are the undesirable results that are getting in your way or stopping you from being the star salesperson? It is a good exercise for the sales manager to ask their salespeople to list at least 10 things and some will have more than that. Be as specific as you can.

Next, once you have this list, you will improve and refine them by asking more questions about each of them. The goal is to improve them so that each UDR is clearly defined and measurable.

Example from above:

- I did not meet my sales quota.

Revised: I only achieved 72% of my sales quota this month and this was the 3rd straight month that I did not achieve my quota. - My customers don’t understand what we do.

Revised: I spend 2 hours, on average, with each pre-qualified prospectto explain what our products are really supposed to do. Our product brochures do not help at all! - It takes too long to get credit approved for the customer.

Revised: It takes an average of 45 days to get credit approved for any new customers and only 60% get approved at all.

So, again the challenge will be to make sure the actual words in the UDR are defined properly (customer, prospect, prequalified, etc.) and measurable (average 45 days, 25%, etc.). We often find

there is no real data behind certain words.

words we are using every day have different meanings to each of us

Learning to think in terms of undesirable results will help you become more successful in your job. Please post a comment and let us know how this idea has helped you. For professional members, this is what SPIF is for. For corporate clients, we can work with you every step of the way to ensure you will be successful at this.

And, before you finish, please do watch this video, for another (somewhat humorous) example of undesirable results.

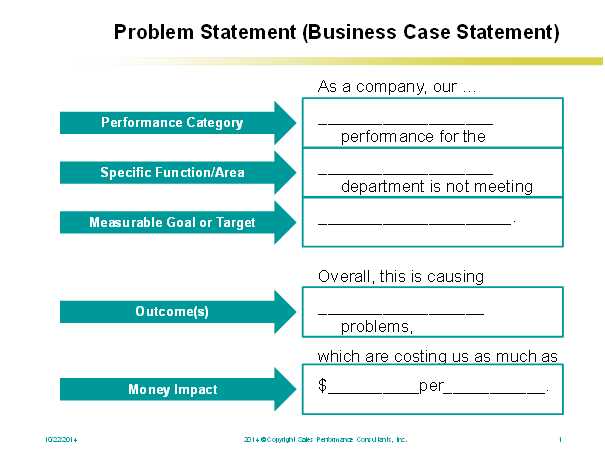

Problem statements (business case)

A problem statement is a statement that follows a consistent structure:

The problem statement ties the problem to the voice of the business, and answers the question “Why is this problem important enough to that it should be prioritized over other problems now, today?”

Problem statements are slightly different if they are focused on internal issues, than if they are focused on customer-facing issues. For example:

[/details]

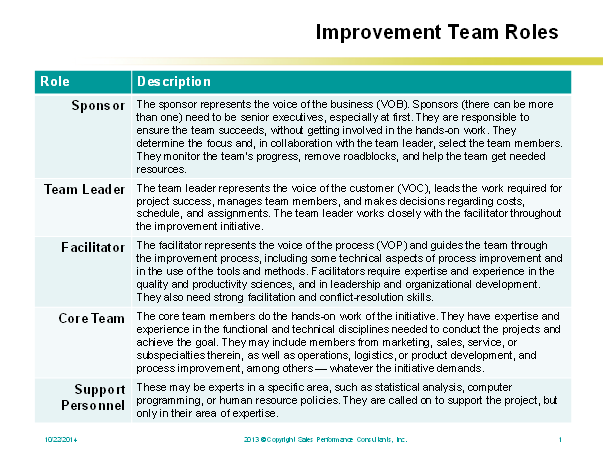

[title]Selecting People for Improvement Team Roles[/title][details]

A key contribution of the sponsor team is preparing the problem statement and setting goals for the core team, which we have already discussed. The sponsors also must select the team leader. If either of these choices is weak or ill thought out, chances of success drop dramatically. Again, this is where good facilitation helps the sponsor team ask themselves tough questions.

All kaizen events and improvement initiatives, small or major, need active executive sponsorship. Executives can dedicate resources and set priorities, and occasionally ride fence for the core team if things get tough. Improvement projects also develop executives with new skills and often profound insights into the business. For continuous improvement to be sustained in your company it must be high on the executive agenda. In continuous improvement companies, you do not become an executive unless you have mastered problem solving and PDCA management skills and can lead improvement at any level and at all levels. Executives are usually the ones usually leading improvement team reviews at the end of a project. This is a carefully honed coaching skill designed to pay respect to the team’s work, yet elevate their thinking at the same time.

Quite often the executive sponsor is in the best position to suggest the best problem statement, and make the case for improvement for the business. If an improvement spans more than one executive’s area, then more executive sponsors should be added, with a practical limit of three. This insures that the project theme is supported by top management before it goes any further.

If you are working the entire gamut of find, win and keep, you may well have two or three sponsors such as VP Marketing, VP Sales, and Director Customer Service. Sponsors also need facilitation. This is because they may not understand continuous improvement, don’t know how to evaluate team progress, or may have unstated agendas that can thwart progress. The facilitator must service both sponsor and core teams, and must have the backbone and skills to handle the carpeted area culture and egos. This at times favors outside facilitators who have no vested interest other than a successful project. They are politically neutral and usually skilled at handling conflict.

Team leader selection and role

The kaizen event core team leader is a crucial choice. Some ways to screw this up are to pick someone who:

- has limited investment in the outcome

- will be disassociated with implementation (deployment)

- is a non-leader type personality for “developmental purposes”

- is pure theorist in marketing or selling, not a practitioner

- the least busy person

- has no time for data and evidence based approaches

The team leader is appointed and commissioned by the sponsor team. He or she is the project manager, and much more. The team leader recommends the core team best able to complete the mission. It is essential that the team leader be able to internalize the mission and research it on her own before embracing the challenge. She will never be able to sell it to the core team members unless this happens. People can spot fakes. The team leader should believe that the task can be done and that the business case is clear, reasonable and has compelling urgency and priority. If you have picked the right team leader, she will ask good questions. Many times the mission has been reshaped by the “catch-ball” process of examination and push-back that occurs. This approach produces a better objective and plan.

The team leader will make assignments to core team members and to others in sub teams or support roles. Support may be needed by market research, or tech support, or customer service or others. The team leader reports regularly to the sponsor team on progress; and at times may need more resources from the sponsor team or to request adjusted work schedules. The team leader enforces discipline to avoid mission drift and loss of focus, something that surely will present itself. The team leader watches the clock and the “fuel gauges” for the team. She will also be there to coach team members on their participation, and to replace them if needed. Smart team leaders know how to “showcase” good work and thank those who have produced it.

The team leader may not know a great deal about specific improvement techniques employed in sales and marketing that come out of the quality sciences, kaizen, lean thinking, or six sigma. That is ok as the facilitator should bring this. The team leader can learn about these techniques JIT (just-in-time) style through side coaching by the facilitator. Above all, the team leader must respect the techniques and demand the same from other participants.

We once witnessed a team leader who had showed up for a sales kaizen event related meeting after surviving a commercial air accident on delta that had killed several passengers. As an ex-marine with combat experience, he had helped the flight attendants deal with the dead and injured before help arrived. This man was such an effective leader and was so well respected, his team mates carried on for him for the first day while he got through the shock of the experience. A good team leader is backed by his team.

Facilitator selection and role

The kaizen facilitator is selected by the sponsor team, with concurrence from the team leader if at all possible. Sometimes the sponsor team will need to pick a strong facilitator not known to the team leader. This may be an outside contracted facilitator, or someone who has had similar experience in another part of the company. The sponsors may want to develop the team leaders skills by teaming her with a seasoned facilitator who may have more business experience.

Facilitators should be the content expert and coach on application of a myriad of scientific business methods, tactics and tools to the problem at hand. A brief sampling is as follows:

- Voice of customer data gathering techniques

- Customer value mapping

- Basic sales process design

- Measurement design for sales and marketing

- Seven statistical tools and software

- DMAIC Problem solving (Define-Measure-Improve-Control) or equivalent

- Kano customer preference model

- Deming improvement cycle for kaizen

- Designed experiments for marketers

Many in manufacturing would see counterparts and similarities in this list; reason being these methods work for all processes and problems. This is not to say one can walk from the plant floor into the lions den of sales and marketing without receiving scratch marks or even with your head still attached. The world of filling demand and creating demand are not the same. The latter contains invisible work, ambiguity, and unknowable results that can be very frustrating to those not trained to handle it.

The sales process IS different!

Even the purposes of sales processes can be very different from those in operations or administration. For example, in sales we may want to set up processes that are sensory to the market and highly action and speed oriented across the sales team; whereas in manufacturing the aim is usually cost, delivery, and reduction in variation and conformity of output. The point is you need a facilitator who has crossed this entire chasm, not a yellow belt from production or supply chain management.

The facilitator must also have the management gravitas to coach and educate both the sponsor team and core team. This is not easy, and is a two-way street where all must leave stripes at the door and work as colleagues who are not above being wrong at times.

Core team selection and roles

These are the gemba worker bees and content experts, the prime doers who will carry the day if the mission is sound and the leadership does its job. Core team members are usually busy people already, because they are of the caliber they keep getting asked to do more. This is why they are a precious resource and don’t deserve to be given the wrong hill to climb or too few resources to be successful.

Typically a kaizen team has 3-5 core team members. More than that explodes the mathematical communication linkages and time required beyond reason. For sales kaizen the typical core team members will come from:

- Market research

- Marketing

- Product management

- Field Sales

- Distribution management

- Customer service

- Information technology

- Product development

- Advertising & promotion

With core team members you are typically looking for traits such as work content knowledge and experience with: the current sales funnel; end-user customer knowledge, industry, global and regional market savvy, web selling and lead generation know-how, product positioning and value proposition expertise, expertise in analyzing the costs of marketing the product, understanding of the industry value added chain, competitor intelligence gathering, economic impact tracking and forecasting, and knowledge of the technology application impacts and trends in sales and marketing. Of course the selection is based in part on the scope and content of the mission at hand.

Other traits can be equally important. There are people who are geniuses that have no desire to be on a focused task team. They should be used as resources, not as core team members. Core team members will need to have the social skills and personal timbre to get information and cooperation from anywhere that is needed. They should be successful scroungers already, like in the prison camp movies where some prisoners can somehow get a few luxuries from pure force of personality and bartering ability. Loners cannot do this. People who are lazy about communications also do not hack it on core teams. They will need to write e-mails at 7pm on a Friday night at times. People who talk too much can drag down a team. Those with poor presentation skills will eat up too much time. You already know who we are talking about; enough said.

Team members can be given standard roles to facilitate the work better. There can be a document control person (a modern scribe); a designated time keeper and schedule enforcer; a scheduler who helps calendarize everyone, and other roles that fit your organization’s style and needs. Spreading the team administration work around helps take the load off of the team leader.

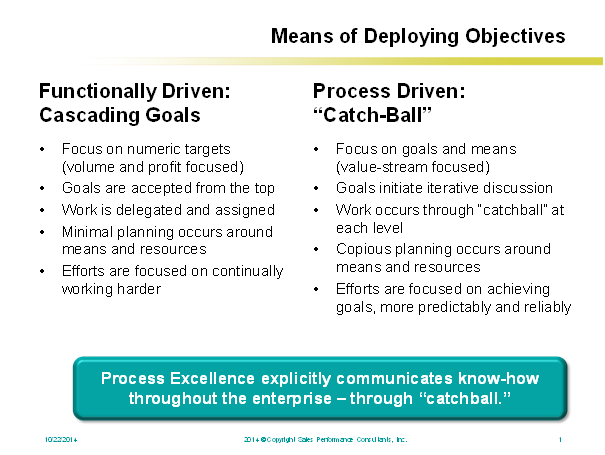

[/details] [title]Understanding the Concept of “Catch-Ball”[/title][details]All businesses need to gain the commitment of their workforce to achieve important business goals. We sometimes describe this as breaking big rocks in to little rocks that one person or small teams can “carry up the mountain.”

In functionally driven businesses the means of deploying plans for achieving goals is described as “cascading.” In process-oriented businesses it is referred to as “catch-ball”. They sound deceptively similar. They are not.

In the Cascading method, top management applies a common goal across business units. A goal such as increasing revenues by 6% in one year is simply assigned to each business unit. Cascading goals is fast and easy. This is the classic approach of little plan and big DO. Although sometimes this approach works, getting the results is often problematic and nerve racking.

In the catchbball method, the same goal is used as a as a starting point. However, top management takes the time to examine the means likely required to achieve the goal. They may break the goal into components associated with specific kinds of means, like new sales, repeat sales, or by market type, or product type.

The goals and means are then packaged together in the beginnings of a plan. The business units then take the lead in examining the goals and means in greater depth, sometimes increasing the size of the goal, or explaining what additional resources are needed. They in turn repeat the process with the next lower level of management. Each level gets the opportunity to “catch” and throw the “ball” back until agreement (and commitment) are reached.

After all have spoken, and top management has signed off, the Plan is now complete. All of the goal components are backed by solid actions that can be taken. Everyone has had time to internalize their part; they know what is expected of them. Precious common resources can now be allocated wisely as needed without waste and fighting. Catch-ball is slow and painstaking. But it will reliably produce results; as the Doing part is much easier.

The story of a resort in the western US using catch-ball is a good illustration. They faced an imperative from city government to reduce consumption of irrigation water for yards and grounds by 10% in one year. Top management at the resort used 15% as its starter goal, and looked at several common means of reducing water usage that could likely produce this improvement. Then they bundled the plan up and sent it to operations management for their input. Operations management, in turn, catch-balled the plan with engineering and yards & grounds maintenance. When the draft plan was presented back to top management, the departments had increased the goal to 20%, and identified many new technologies and methods. Actual results over three years were a 50% reduction in water usage, over 1.1 million gallons per year. The resort won the first place award in the city for water conservation in 2004, a heavy drought year, and now holds clinics on water conservation.

[/details] [title]Using an Improvement Frame[/title][details]Using An Improvement Frame to Create an

“Operational Definition” of a Critical Initiative

|

What is in it |

Why this is needed |

|

|

Objectives:

Background,

UDRs,

Problem statement Goal statement |

An externally (i.e., customer) focused description of:

|

Provides necessary context so people understand what has come before this.

A simple, direct statement of purpose is generates alignment and understanding. To define the problem in terms of data, not causes or presumed solutions The best way to understand why you are doing something is to clearly define what you expect to get out of it. |

|

Methods: How will you create this improvement? |

A statement describing the basic approach the team believes will solve the problem or achieve the goal. |

This gives the basic direction for the work, such as indicating which of the four problem types you are dealing with and how it will be approached. |

|

What outcomes or effects do you expect? |

A description of the changes in roles, structure and function that will take place in the organization as a result of successfully completing the initiative. This often includes specific “deliverables.” |

Provides insight into how people hope things will look and feel after the initiative is completed. In a sense it creates an “updatable vision” and helps everyone agree on what the initial version of that vision is. |

|

Define the scope (boundaries): |

A set of statements which define what is “fair game,” what must be addressed, and what should not be touched in carrying out the initiative. |

This section addresses many of the reasons why initiatives falter

|

|

Measures: How will you know you improved? |

A set of specific quantities which will be measured and used to assess how well the initiative has been carried out and whether the goals have been achieved. |

Provides the answer to the question “how are we going to know if this thing works?” The measures operationally define some of the goals listed earlier. It also pinpoints the baseline data needed. |

|

Problem Solving Plan: |

A list of key points which provide a 10,000 foot view of how the initiative will be carried out. Usually provides guiding information on timing, phasing, what happens before, during and after the work, and how it will be managed. |

This provides a rough framework for answering the question “how are we going to do this?” It is often necessary for the Core Team to create a more detailed plan. |

|

Roles |

A table of key roles and the people who will fill them in carrying out the initiative. These usually include team leader, facilitator and team members for both the sponsor and Core Teams. |

This section assigns responsibilities and therefore “accountability.” It also helps identify what capabilities and skills are needed to move ahead. |

–Improvement Frame Example (V3).doc

–Improvement Frame Template (V3).doc

[/details]

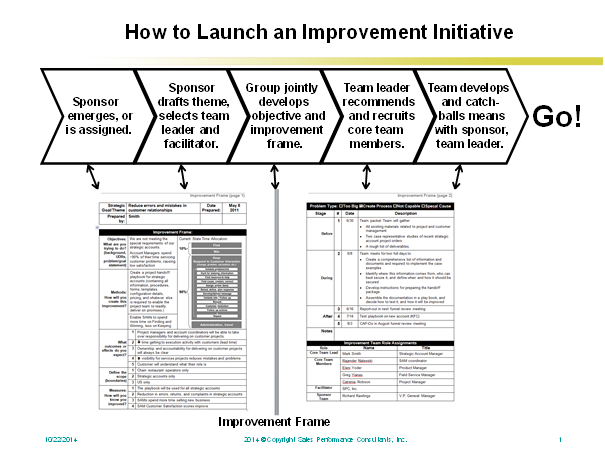

[title]Launching an Improvement Initiative[/title][details]

With clear sponsorship from management, and careful thought and discussion through catchball, leaders can generate enthusiastic ownership of problems and energize teams to solve them. Often, such teams can accomplish far more than anyone previously thought possible.

To achieve this healthy situation, the proper sequence needs to be followed to launch the improvement:

This launch sequence leverages the improvement frame through each step. Often numerous iterations of the improvement frame need to be completed before the team settles into a thorough and shared understanding of the problem, and how to go about solving it.

Giving the team the time and support necessary to launch an improvement correctly is more than half the battle of succeeding with process excellence.

[/details][/accordion]