SPIF Tips #32: The Root of Improvement

I recently had the

I recently had the

opportunity to talk with Bob Miller, former Executive Director of the Shingo Institute. I asked him how he helps companies change their culture in a manner that enables improvement to really stick.

His answer was quite interesting:

Most people have a natural instinct to want things. They want better, easier, simpler, and faster. They want to remove barriers, and to get rid of frustrations in their work. In the Shingo Model we call it the principle of “Seeking Perfection.”

I try and help leaders to tap into that natural instinct. Once people realize it applies for their own goals and desires, you can build on that. That’s because the best way for them to achieve what they want is the principle of “Scientific Thinking.” Which is another principle in the Shingo Model. So how can you encourage Scientific Thinking? The discussions expand deeply from there.

He just named the root of all improvement. The effective executive asks his or her people “What do you think should be improved?” And, “How will y ou do it?”

ou do it?”

From there, you can examine their thinking. Of course you hope people grasp the essentials of the scientific method from their schooling. Yet, even if they’ve studied the “hard sciences” this presents the opportunity to discuss their thinking, especially when it comes to something you, or they are unfamiliar with. This is where executives can be most helpful.

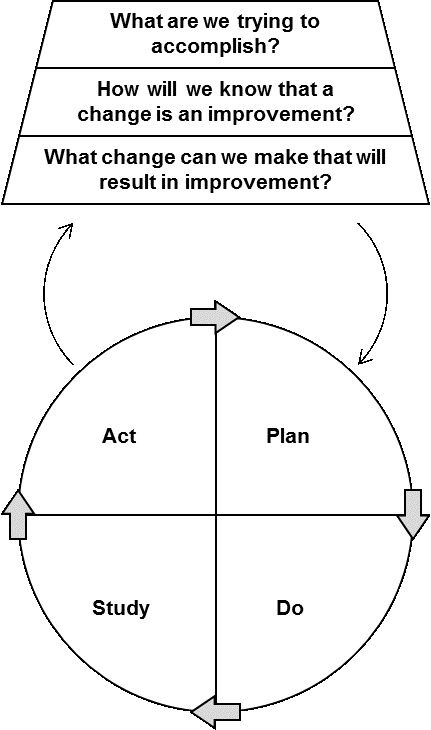

A profoundly powerful model executives can use to do this is in The Improvement Guide, 2nd Edition.[1] It is called the “Model for Improving.”

As children we naturally learn to use language to observe and experiment. As we get older our words and concepts get more abstract. We can easily “lose our place” or “drop the context.”

For example, suppose your dog has the annoying habit of running out the door when a delivery person comes. You want the dog back in the house. It would be an improvement if he were to come to you instead of running away. You try yelling “Come back here!” The dog runs away faster.

The model for improvement illustrates what you should be doing to succeed. Knowing this enables you to compare it to what you are really doing. Why doesn’t yelling or chasing the dog work? Because the dog behaves fearfully. Is there something else that might work better? Leash the dog, or train it to come when called.

The model for improving keeps your mind in contact with reality. It is the work that is necessary for survival. (As a fun exercise, try to compare the steps in the model with the statements in the example.)

Usually, when people don’t learn from their experiences it is because they fail to follow the model. They don’t check or study their results. They don’t think about what the causes might be. They do not realize their mind should be doing this. So they keep making the same mistakes.

The same thing happens on a much grander scale within companies. Who hasn’t had the experience of coming back in contact with a company after several years only to realize it is struggling with precisely the same chronic problems it had previously? Who hasn’t seen the company whose culture causes them to obsess over planning, at the expense of doing, or vice versa, but in every case ignores checking/studying and acting? Lack of improvement is a dead giveaway the model isn’t being followed.

To be sure life’s problems get more difficult and complex than dog chasing. Once you grasp what your mind should be doing you can help others do the same. The model is so simple it scales beautifully. It was first described by Deming in his books. It has since enabled millions of people around the world to collaborate and solve incredibly complex technical and organizational problems. It is responsible for billions of dollars of profit and waste reduction in organizations around the globe. It is responsible for the continued success of remarkable companies. The same principles apply, whether you are a kid who wants to learn baseball, a salesman who wants to get customers to buy, or a CEO trying to help dozens of executives achieve their business objectives.

I would call this a philosophic model, because it applies so universally.[2] It is the foundation of the quality and productivity sciences. It is what people were doing that enabled them to develop all the tools of Lean, Six Sigma, The Shingo Model, and everything else that works.

In fact, if you have tried to teach the tools of Lean[3] or Six Sigma[4] to people, you’ve probably caused some of those people to run away like an untrained dog when the door opens (especially salespeople ;-). Of course, they’re human, so they might not let you know they are doing it at first.

The reason people run away from these situations is that practitioners start with tools and theories instead of what is important to their students. What do you think would happen if instead they started with the Model for Improving?

What are we trying to accomplish?

How will we know a change is an improvement?

What change can we make that will result in improvement?

Most often, asking these questions moves practitioners a step closer to winning other people’s hearts and minds. Everything else follows from there.

About the Author

More than twelve years ago, with deep experience in field sales, sales management, and sales training, Michael Webb set out to create a data-driven, process-based alternative to the offerings of typical sales training, sales consulting, and CRM companies. Since 2002, he has published numerous articles on ways B2B sales organizations can benefit from process improvement techniques, and consulted with companies like All Printing Resources, Burr Oak Tool, Danfoss, Wacker, Pentair, as well as many other B2B companies.

His newest book, Sales Process Excellence earned the Shingo Research Award in 2015. Learn more at www.salesprocessexcellence.com. Michael can be reached at www.salesperformance.com/contact-us

[1] The Improvement Guide, 2nd Edition, by Langley, Moen, Nolan, Nolan, Norman, and Provost, 2009, Jossey-Bass, pg 24.

[2] Because of the way it is taught in schools, most people think philosophy isn’t useful in our world because it tries to tell you how little you really know. Unfortunately, to succeed in life you really have to know a lot of things. In my view however, philosophy is what enables the hard sciences to work. It is the miss understanding and misapplication of philosophy that causes the “social sciences” to be “soft.”

[3] Specify Value, The Value Stream, Flow, Pull, and Perfection; (Lean Thinking, by James P. Womack, and Daniel T. Jones, Simon & Schuster 1996)

[4] Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control; (The Six Sigma Way, by Peter S. Pande, Robert P. Neuman, and Roland R. Cavanagh, McGraw Hill 2000)