SPIF Tip #36: Unless You’ve Gone to the Gemba, You’re Probably Fixing the Wrong Sales Problem

I’ve often written about

I’ve often written about

the sad state of affairs in sales and marketing productivity. It happens because companies have only anecdotes and no data on the causes of sales and marketing problems.

But collecting and analyzing data is harder than it seems. The “information dashboards” and “control systems” guiding and controlling sales and marketing are notoriously bad. Salespeople don’t like to collect data. And unless you have some background in process improvement, you may be unable to use the data you have.

So, where do you “Go to the gemba” in sales and marketing?[1] Where you start in analyzing data?

Whether you want to improve sales productivity, or manufacturing productivity, the most important part of the system is the people. In both arenas, you must start by studying what is between the ears of your employees. Before sales and marketing people can help you improve things, they need to know why they are doing it, and what is in it for them.

The WIIFM for employees is the possibility of fixing a system that is likely broken today. Symptoms of broken sales and marketing include things like marketing promotions, websites, and emails that no one reads, lead generation that doesn’t work, and proposals that don’t get bought.

If you could lighten everyone’s load by eliminating these wastes, they would have more time to work on more of the things that count. Before you can do that you must enable the team to achieve a common understanding of the problems that need to be solved.

Where is the problem located?

In this early stage, we use a self-assessment to help locate and clarify sales and marketing problems. We ask individuals such as product managers, marketers, salespeople, and their managers to use a 1 – 5 scale to rate various aspects of their environment. Below are the responses from two different companies. Neither company is happy with its sales growth.

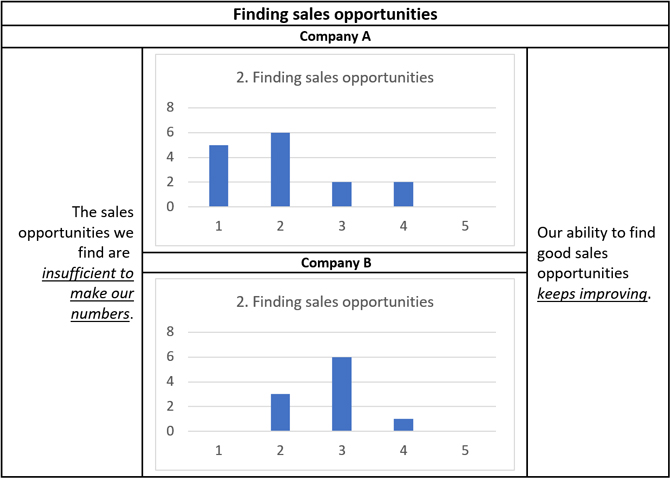

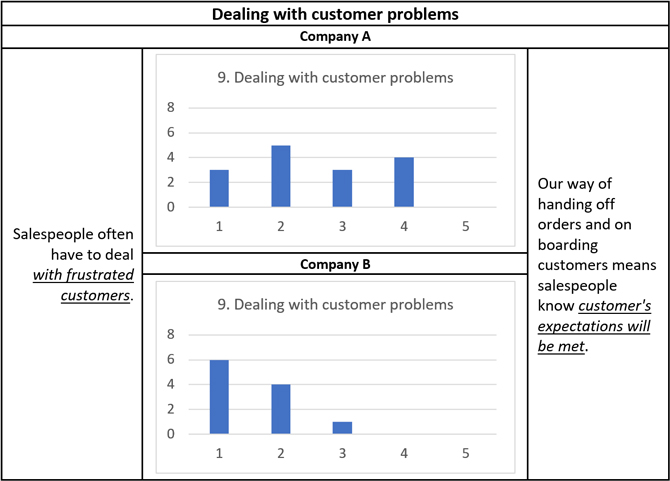

Figure 1 shows the responses of both companies to a question about “Finding sales opportunities.” Figure 2 shows their responses to a question about “Dealing with customer problems.”

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Company A seems to have more of a challenge finding opportunities (Figure 1). Company B seems to have more of a challenge dealing with customer problems (Figure 2[2] ). Notice anything else?

Company A’s participants seem to have less agreement among themselves than Company B in general.

Of course, you would ask the participants from both companies what they thought the question was asking about, and why they answered the way they did. Participants are usually interested in each other’s answers. These discussions help everyone understand the company better.

However, variations in the responses are clues that there is more we need to know, as we will see. Unfortunately, many executives don’t even gather even this much information, much less listen to employee’s perceptions in detail. They prefer to “shoot from the hip,” and that can cause big problems.

I told a true story about this kind of situation in Chapter 12 of Sales Process Excellence. Vargus Communications (not its real name) was a $400 million company that hired a new president with a stellar pedigree to grow its business. He and the management team decided their salespeople were spending too much time with existing accounts. They wanted salespeople to bring in new accounts.

They did not engage people in identifying problems or discovering causes. Instead, they rearranged sales territories and revised compensation plans.

The result? Vargus collapsed within a few years. The reason? Those salespeople were spending so much time on existing customers for a reason. Forcing them to call on new accounts attempted to solve the wrong problem.

My guess is that had Vargus employees taken the self-assessment, their answers would have revealed the “Dealing with customer problems” Issue. In addition, a number of their responses would have shown wide variation – like Company A. There is a reason for this, which we’ll get to momentarily.

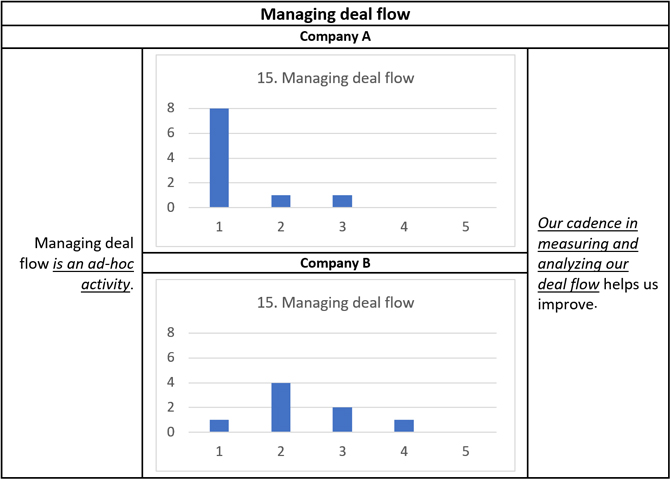

First, consider Figure 3, which shows responses to an entirely different kind of question about “Managing deal flow.” Company A’s participants are lined up way on the left-hand side. On the other hand, Company B’s participants are more mixed and trend toward the middle. The response is spread wider, indicating disagreement.

A discussion among the individuals in both companies is called for. Is there frustration from a new CRM (or an old one)? Is there frustration with sales management (or lack of it)? Since managing deal flow is a broad topic, it is usually a very productive discussion. Whatever is behind the responses in either company needs to be examined before management decides what kind of intervention will create improvement.

Figure 3:

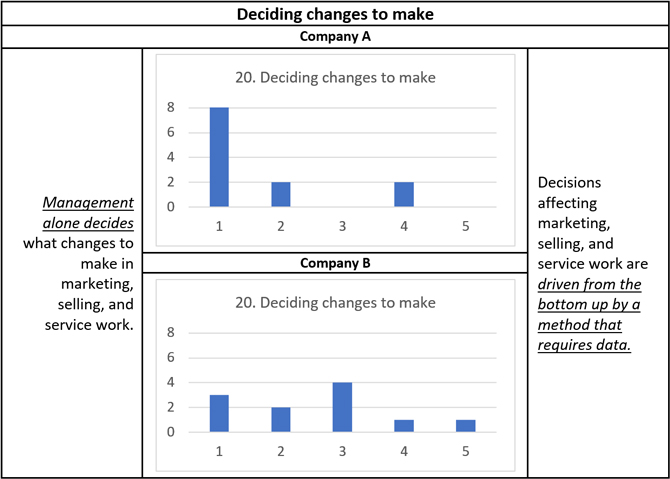

Now, consider the last diagram, Figure 4, “Deciding what changes to make.” Company A’s employees seem to perceive a rather authoritarian environment. If this is not what management intends (and it usually isn’t), then why does the data tell us something different? If management wants things to change in the company, some thought and consideration around these responses might be in order.

Figure 4:

Company B’s responses show and entirely different situation. Why are the responses spread out all across the range? Helping participants to isolate the instances and examples they were thinking of helps increase everyone’s understanding.

Time spent reflecting on questions like these is usually well spent. It helps bring up crucial issues, like “What does accountability mean to us?” and “What is management’s role, versus the salesperson’s role?”

Improving everyone’s understanding of the answers to such questions is good for the business. It helps people get in better touch with each other. And this is what enables people to see why change is needed, and what improvement might look like.

Conclusion

Superficial business pains like, “We need more qualified opportunities,” or “We need better customer service” are often obvious. However, fixing such problems is more difficult than it appears. That’s because until the systemic causes are identified you can’t make changes in a way that can be sustained.

And you can’t identify them if you don’t take the time and effort to “Go to the gemba,” as they say in Lean.

Lean sales and marketing is not intuitive because the “Gemba” is between people’s ears. That doesn’t mean it is not knowable. It merely means you and your employees must develop a way to see it and to know it. You can engage your people in identifying problems and discovering causes. It is the only thing that can make the information in a company’s CRM or other dashboards meaningful.

What guidance have you tried to follow in solving your company’s sales and marketing challenges? And how well has it worked? I’ll look for your thoughts in the comments below.

Also, if you’re curious about the self assessment we use, contact me – “Your Most Important Question”.

[1] A Japanese term meaning “the real place.” Japanese detectives call the crime scene gemba, and Japanese TV reporters may refer to themselves as reporting from gemba. In business, gemba refers to the place where value is created; in manufacturing the gemba is the factory floor.

[2] Sharp-eyed readers might notice there are 15 Company A participants in Figure 1, and 16 in Figure 2. This is because one participant selected the “Don’t know” response, which does not show up in the charts.